Electrical safety features

This page documents the safety features found in modern-day electrical installations, how they function and the danger posed by older or non-compliant items where they may not be present.

Note that, ideally, all of these protections should be present in an electrical system, regardless of the voltage used in a specific country. Mains voltage, be it 100 or 240 volts, can and will kill you and shouldn't be used as an excuse to be careless in the design of an electrical system.

Dangers present in older items

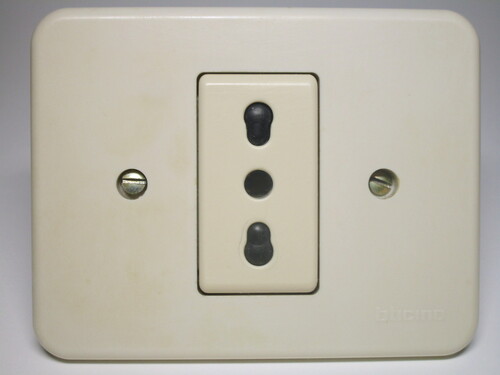

The plugs and sockets shown below are an example of the dangers commonly present in old electrical items:

The first two images showcase a common issue with old power sockets: the exposed metal contacts. The design of these items means that it's trivially easy to touch the live contacts inside, either with a finger or with a metal item, and thus receive a (potentially fatal) electric shock.

Safety issues were also present on old plugs: the third image shows a partially inserted plug, where the pins are already making contact and thus live even though a significant portion of them is still exposed and very easy to touch when inserting a plug, especially if not looking.

Safety shutters on power sockets

Safety shutters found on power outlets prevent someone from coming in contact with a live connection, even if using some sort of metal object like a screwdriver. They also prevent someone from inserting only one pin inside a socket and thus making the other one live.

The adoption of shutters isn't universal even within Europe, however they're generally found in power strips and extension cords, and they're compulsory in some countries such as France, Italy, Denmark and the UK. In the US shuttered sockets, which are referred to as TR (tamper-resistant), have recently started being mandatory on new builds, but it's still possible to buy ones without them, and they're not at all common on power strips or extension cords.

Shutter mechanisms can work in various ways, but the key feature found in all of them is that an electric

shock should only be possible if using two objects: one to open the shutters and one to actually reach the

live contacts.

Three different types of shutter mechanisms are shown here, each functioning in a slightly different way:

The operation mode of all of these is the same: the two pins of the plug will cause the shutters to slide open if pushed at the same time, while a single object wouldn't be able to make them open due to friction.

The main difference between the three mechanisms is the way the shutters move once a plug is inserted: in the first one they simply rotate to the side, while on the second and third one they slide either to the side or downwards.

A different style of shutter mechanism is in use on certain 3-pin plugs and sockets, namely the UK ones (BS1363), where this is required, and in modern-day BS546 ones, but also on some Australian-style sockets found in China, where those plugs are only used for devices that require an earth connection. With this type of mechanism, the shutters for line and neutral will open by the insertion of the earth pin, which thus has to be slightly longer.

This style of mechanism is in some ways better, as if someone were to get a shock they'd be in contact between line and earth, allowing an RCD to trip. However, it also requires all plugs to have an earth pin, which can make them quite bulky.

Notably, some higher-end British sockets use both methods, with the shutters only opening if the earth pin is in place and then by the simultaneous push of the line and neutral pins.

Sleeved pins and recessed sockets

As seen earlier, with older plugs and sockets it was quite common to have the pins be easy to touch when partially inserted inside a power socket, thus creating a shock hazard (especially if holding the plug with wet hands, such as for a hairdryer). As such, most plug and socket systems around the world have, over time, been improved in order to make it impossible to touch live pins on a plug, by using either sleeved plug pins or recessed sockets.

It should be noted that, in order for either of these systems to be truly effective, plugs and sockets have to be designed for one another; effectively considering the two not as separate items but as an interface. This can be noted on some very old sockets with contacts right up to the surface: with those, even a modern plug with sleeved pins may still leave the pin live when partially inserted, as the socket has contacts too high up compared to modern-day ones.

On plugs with sleeved pins, the socket remains substantially unchanged while the pins of the plug become partially covered by an insulating material, in such a way that, while making contact with the socket, the only part exposed will always be the sleeved part of the pins.

This system is used on Europlugs and on British (since 1984), Italian, Swiss and Australian plugs, as well as on some Japanese ones (though non-sleeved ones are also commonly used), among others. It should be noted that both on the Swiss and IEC 60906-1 standards this is combined with recessed sockets in order to provide the most protection.

Recessed sockets, on the other hand, move the problem to the socket end: the socket must have a recess of a certain depth in order to make it impossible to reach the pins while the plug is live. The most well-known examples of this style of sockets are the Schuko and French-style ones.

This approach offers a larger contact area on the pins than on plugs with sleeved pins, as well as a much more firm connection, which can be useful for things like wall-warts and timers. However, its main downside is that it requires the use of a compliant socket in order to provide this protection; as such, older sockets (generally, unearthed ones) and some cheap travel adaptors may allow the plug to connect while leaving part of the live pins exposed.

Protective earth (ground) connection

This important safety feature ensures that all exposed metal components of an appliance are connected to an earth conductor, which has to be the first connection made when plugged in and the last to be disconnected.

Thus, if the appliance has a fault, like a damaged wire, that causes its chassis to become live, a current will flow to earth. This will cause an automatic disconnection device to trip; a fuse or breaker for high-current faults, or an RCD for low-current ones. The result is that power to the device will be interrupted, preventing someone from potentially coming in contact with it and receiving a potentially fatal shock.

Because of its importance, most countries around the world now mandate new circuits to have an earth connection and the use of earthed power sockets, though older installations may still have non-earthed circuits and outlets. In order to enforce this protection, plugs used for earthed appliances often ensure that they cannot physically be connected to such outlets, generally by the use of an earth pin, though notably the Schuko and French-style plugs most commonly used in Europe allow their connection to the older style CEE 7/1 sockets, due to the way earth connections work on these types of plug.

It should also be noted that the way earthing systems work and are set up can vary substantially between different

countries and electrical codes, and, in some places, even within the same nation.

In short, these systems can be divided between TN supplies, where the earth is physically connected to the

neutral at some point, and TT supplies, where the earth is only connected to an earth rod.

A detailed explanation of the way various supplies provide a protective earth conductor, as well as their various pros and cons is present in a separate page.

Double insulation

Double insulated (Class 2) appliances offer protection against a single failure without relying on an earth connection, by using reinforced protective insulation (such as two layers of plastic). This is as opposed to Class 0 appliances, which offer no protection even after a singular failure; such devices have long since been made illegal in 230V countries, though they may still be found on older items, most commonly with incandescent holiday light string sets.

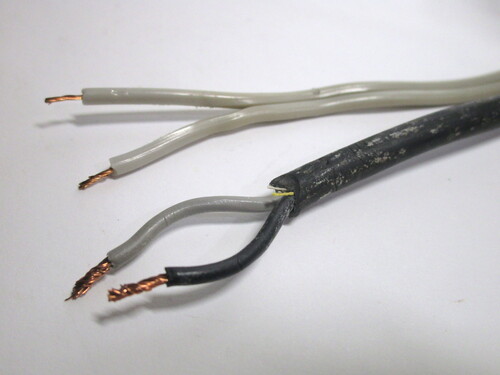

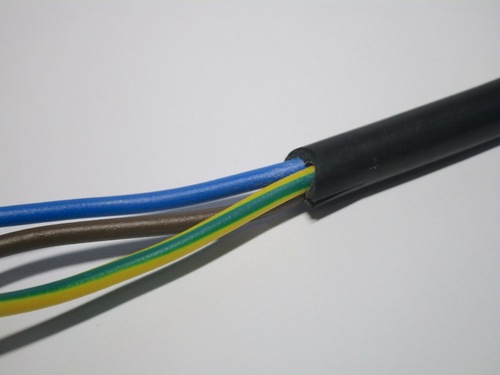

In particular, one good example of this practice is in the double insulated power cords, which are the only type in use in Europe nowadays. With these, the application of this principle is very clear: in addition to the standard insulation around the wires an additional protective layer of plastic is present around them, so a simple cut to the cable is unlikely to reveal the live conductors.

Unfortunately, single-insulated cables are still very common in 120V countries, generally being used for non-earthed appliances and cheap extension cords.

Residual Current Device (RCD) / Ground Fault Circuit Interrupter (GFCI)

As the name implies, these devices offer additional safety features in order to protect a user, but shouldn't be relied upon to be the only form of protection. With RCDs, where this term is more commonly used, this is because, while they generally protect someone from electocution, they still require a person to receive a shock in the first place.

These devices monitor the current flowing in the line and neutral connections; normally, their sum should be zero, however in case of a fault, such as someone touching a wire, the current may take a different return path. This will then be detected by the RCD and, if above a certain limit (typically 30mA), will disconnect immediately in order to stop a potentially fatal electric shock.

RCDs have made a significant contribution to the safety of electrical installations over the last few decades, and as such are required in new installations on a large number of countries worldwide.

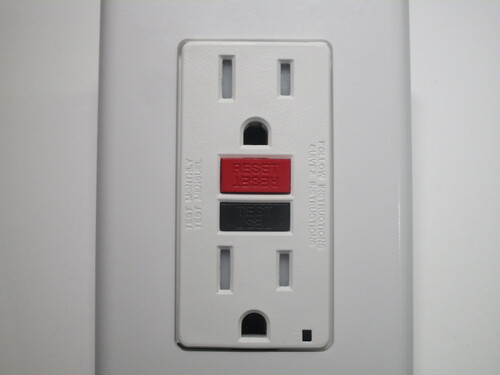

While their theory of operation is the same, there are some significant differences between European RCDs and American GFCIs: the former are typically installed in a breaker panel in order to protect (either individual, or multiple) circuits; as such, it is possible to protect an entire installation for a relatively low price to the customer. They're available in either "pure" (RCD-only) devices or RCBOs, which also incorporate a breaker; it's also common for these devices to interrupt the neutral conductor.

American GFCIs on the other hand are generally found in sockets (something also available in Europe but less commonly

used), which protect the outlet on the device itself and any others connected to the load terminals.

GFCI breakers are also avabilable, the equivalent to a European RCBO, though they're less commonly used.

Notably, GFCIs trip at 5mA, compared to the 30mA of RCDs in Europe; however, they're much less commonly used,

generally being installed only in wet areas such as kitchens and bathrooms.

Dangerous adaptors

Poorly made travel adaptors can pose a significant danger due to the poor connection at the socket end; this can lead to high resistance connections to be made which can then melt the adaptor, creating a fire risk.

Additonally, most of these adaptors don't offer any safety shutters, which often also means it is possible to insert a plug with one pin only, leaving the other one live and very easy to touch. It's also fairly common for adaptors to bypass the earth connection on the socket, which can create safety hazards when earthed devices are connected.